Twin gaps of skills: Learners’ aspirations and the contents of school educationShoko Yamada

As I mentioned in my previous essay (https://skills-for-development.com/essay/fkgskm?en), people’s ability to finish their schooling and look for jobs does not match the expectations of employers looking for talent because of the mismatch between the supply and demand of industrial human resources. There are two types of inconsistencies. One is the so-called “vertical gap” in terms of length of schooling (academic background), and the other is the inconsistency in terms of content (the “horizontal gap”), where the range of skills does not match the demands of the labor market. These vertical and horizontal gaps are another way of looking at the gap from two different angles: the length of schooling (pre-employment education) received before employment and the knowledge possessed by the job seeker. This indicates that whether or not one has received teaching and the amount or quality of learning are different things.

Focusing on the years of schooling, the gap with the labor market can be seen as a problem of over-or under-education, as discussed previously. One reason for this is that schooling is the most readily conceivable way to develop human resources and bureaucrats responsible for national policymaking. At the same time, these ideas have been reinforced by theoretical methods. Many studies based on the theory of human capital, which considers human resources as one form of capital that can contribute to the development of a country and improve individual income, have used the number of years of schooling and the major field of study as indicators of human resource capacity.

According to the concept of labor economics, in the labor market, an employer expects a worker with particular attributes to be able to do a specific job. Based on this expectation, the worker is given a job and paid a wage. Suppose the worker is expected to have a high level of expertise and workability. In that case, the employment opportunities will expand. If the worker performs in line with the employer’s expectations after employment, the worker will receive incentives such as career advancement and salary increase. In this case, it is assumed that there will be a direct exchange between the worker’s ability and the wage paid by the employer, with the worker on the supply side and the employer on the demand side.

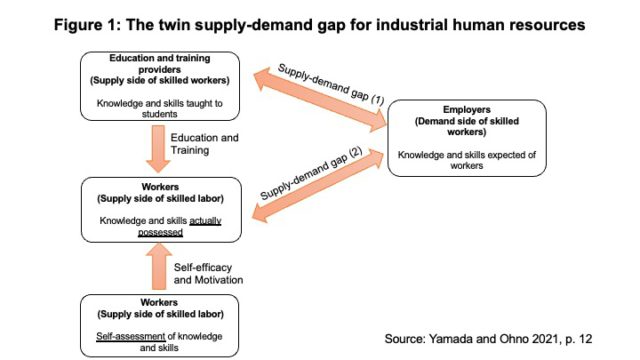

However, there is a slight discrepancy between these ideas of labor economics and the actual situation in the discussion on human resource development. Institutions that provide education and training (vocational training schools, high schools, universities, etc.) are the ones that supply the human resources that pass school education and enter the labor market, but especially in the case of developing countries, the content and policies of the education provided by these institutions are often determined based on the human resource development plans of the government. In such cases, the debate on the human resource skills gap has led to an awareness of whether human resource development undertaken as a national development strategy fails to meet employers’ expectations and how to modify the policies and curricula.

Even in the latter case, a double supply-demand gap can exist: (1) the gap between the job the worker wants to do and the skills they think are necessary for it and the skills needed by the employer. Even in the latter case, there can be a double gap between supply and demand: (1) the gap between the skills that workers themselves want and need for their jobs and the skills that employers need, and (2) the gap between the skills that institutions and teachers who train human resources think are essential and the skills that employers need.

For example, in our survey (Yamada and Otchia 2020) at a vocational training school in Ethiopia, we found that many of the students wanted to start their own business after graduation. In contrast, the teachers at the same school wanted the students to learn management and organizational skills and design and marketing skills in the field they majored in at school (sewing in our case). In contrast, teachers at the same school did not consider it essential to teach students how to start their own business after graduation and tended to focus on manual skills directly related to manufacturing, such as machine sewing, pattern making, and measurement of clothing size, which are required in factory production lines. In particular, relatively older teachers who had not received training in new educational methods and had little contact with industry tended to focus on these manual skills, suggesting that as they repeated the same tasks over and over again, they became less aware of the need to link educational content to students’ career aspirations and changing labor market needs. After years of working in the same job, this suggests that some teachers have become less aware that the content of their education should be linked to students’ career aspirations and changing labor market needs.

References

- Green, Francis and Steven McIntosh (2009). Is there a genuine under-utilization of skills amongst the over-qualified?, Applied Economics, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 427-439.

- Pellizzari, Michele and Anne Fichen (2017). A New Measure of Skill Mismatch: Theory and Evidence from PIAAC, IZA Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 6 no. 1, pp. 1-30.

- Yamada, Shoko and Christian Otchia (2021 forthcoming). “Differential Effects of Schooling and Cognitive and Noncognitive Skills on Labor Market Outcomes: The Case of the Garment Industry in Ethiopia” International Journal of Training and Development.

- Yamada, Shoko and Christian Otchia (2020). “Perception Gaps on Employable Skills between Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Teachers and Students, and Their Causes: The Case of the Garment Sector in Ethiopia”. Higher education, skills, and work-related learning.

- 山田肖子・大野泉(2021)『序章-今なぜ途上国の産業人材育成か』山田肖子・大野泉編「途上国の産業人材育成-SDGs時代の知識と技能」日本評論社.